“Courage! I have shown it for years; think you I shall lose it at the moment when my sufferings are to end?” – Marie Antoinette

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Spotify | Amazon Music | Youtube Music | RSS

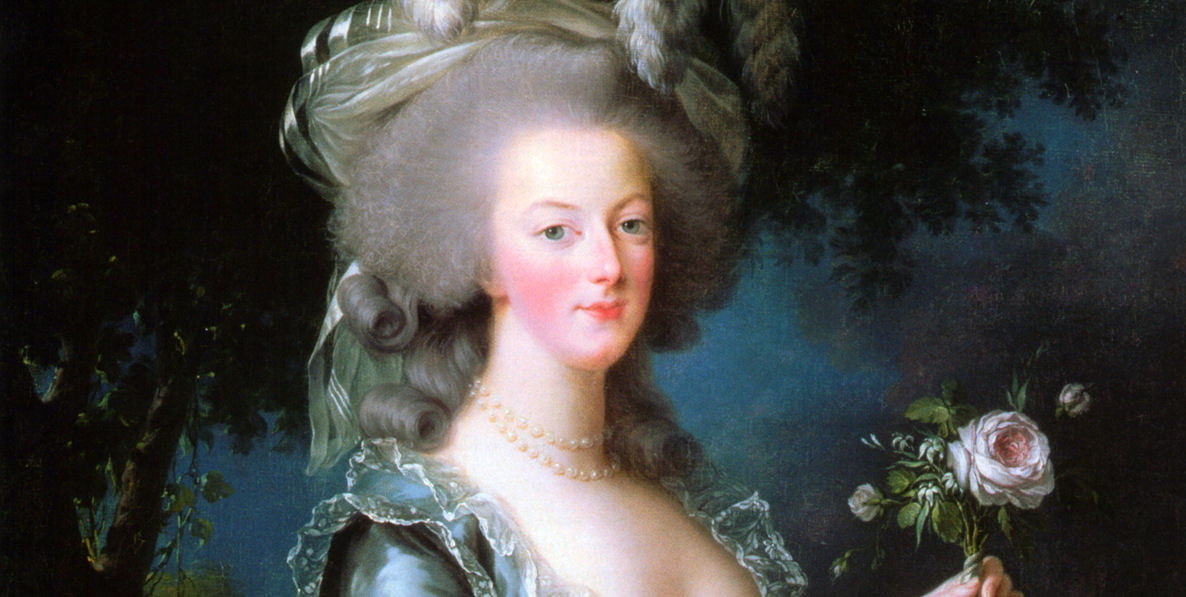

Marie Antoinette Biography

“S’ils n’ont plus de pain, qu’ils mangent de la brioche!” – translated, “If they have no bread, then let them eat cake!”

These words came to symbolize an individual’s, and a government’s, callous and supreme indifference to the well-being of its people. They are attributed to Marie Antoinette, Queen of France and Navarre.

But Marie Antoinette was not raised to be an extravagant, indifferent, and entitled person.

She was born Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna on November 2, 1755. The newest Archduchess of Austria was the 15th of 16 children born to the Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa and Emperor Francis. And like her sisters, she would become one of the royal political pawns whose marriages would shore up the numerous alliances forged out of the Seven Years’ War. Maria’s marriage to the future king of France was of particular importance because it would help strengthen the alliance between former long-time enemies, France and Austria.

Maria’s early childhood was spent in the relatively relaxed court and private life in the Hofburg. She was educated in languages and history but perhaps she was an indifferent student in the academic subjects. Her reading, languages, and writing skills were still poorly developed by the age of 10.

Maria, known as Antonia in the Austrian court, shone more in the arts and graces – manners, dance, music, and drawing. Antonia excelled in music and dancing, and sang from the French and Italian repertoires. She also played spinet, clavichord, harp, and harpsichord.

In 1767, negotiations were initiated for a marriage between 14-year-old Louis Auguste, Dauphin of France, and 12-year-old Maria. The process of becoming a royal wife-to-be was not simple, or comfortable: someone had noted that her teeth were crooked and it was mandated that she have corrective oral surgeries. Over a 3-month period, a French doctor completed the surgeries on Maria, without anesthesia. Finally, her smile was determined to be, “very beautiful and straight,” and the negotiations continued.

She and Louis Auguste were married by proxy in an Austrian church on April 19, 1770. She departed for France two days later and was married in the Chapel Royal at Versailles on May 16, 1770.

If the road to marriage was challenging, the road to becoming a popular wife, queen, and mother were even more so. The French citizens were initially captivated by the new young and pretty strawberry blonde dauphine but this popularity was short-lived. The marriage was not particularly well received at court where long-held distrust of Austria had not been assuaged.

Her new husband had been a scholarly and physically active child. As a bridegroom, he seemed more interested in his lock-making and hunting hobbies than his pretty young bride. Much has been written about the seven years between the royal marriage and the birth of their first child. With his seeming indifference to her, Maria (now Marie Antoinette) began indulging in the profligate behavior – gambling, expensive clothing, partying – that would condemn her forever in the eyes of her subjects.

Her mother’s criticism regarding Marie’s shortcomings as wife were followed by a visit from her brother, the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph. At some point, Joseph counseled his brother-in-law, later commenting to his brother Leopold that the king and queen of France were, “a couple of complete blunderers.” They apparently benefitted from Joseph’s counsel as Marie became pregnant with their first child eight months later.

Marie Thérèse Charlotte, Madame Royale, was born on December 19, 1778. Marie had given birth (an exceptionally difficult labor) in view of countless numbers of courtiers in the bedchamber. Marie vowed never to endure such a public ritual again. Most courtiers were banned from the bedchamber during subsequent labors.

Despite the king and queen’s personal delight in the birth of their daughter, the Queen’s failure to produce a male heir further diminished Marie’s popularity. Even the birth of their second child, the much-desired Louis Joseph, Dauphin of France, would not improve her standing in the court or with the public. (Louis and Marie would have two more children – Louis XVII, Titular King of France and Navarre, and Princess Marie Sophie.)

Almost from her arrival in France, Marie Antoinette had been the subject of criticism and venomous ridicule. Libelles, political pamphlets that were the social media of the day, relentlessly criticized her every relationship, expense, her political influence over her husband, and held her directly responsible for the financial collapse of the nation. Yet how realistic were these criticisms?

Early on, the French people began referring to her as “L’Autrichienne” – the Austrian bitch. Admittedly, Maria Theresa had counseled her daughter on the importance of expanding the alliance between France and Austria, but in truth, Marie had little political influence over her husband.

Condemned as extravagant, “The Affair of the Diamond Necklace,” filled the libelles and further fueled the public’s animosity. The case of a costly diamond necklace, allegedly ordered by the queen but not paid for, went to trial. Although the queen was innocent and exonerated, the scandal added more damage to her now-fragile reputation. Ironically, Marie Antoinette had become far more conservative in her spending, behavior, and attire once she became a mother.

The Diamond Necklace scandal has been credited by some as the triggering point of the French Revolution. But the nation had been deeply in debt for many years. France had been a major participant in the Seven Years’ War and a financial backer of the American Revolutionary War. France also had suffered years of bad harvests and a tax structure that placed undue burden on the middle class and peasants. The king had pressed for tax reform but the Council of Nobles remained intransigent to any reform.

Ultimately, the monarchy was pulled apart in 1792 by the revolutionaries. The king and queen and their two surviving children (the Dauphin had died of tuberculosis and their youngest, Sophie-Béatrix died before her first birthday) were arrested and imprisoned in Paris where they were declared “enemies” of the revolution.

The king, now known only as Citizen Louis Capet, was tried and condemned for high treason; he was executed on January 18, 1793. Marie Antoinette, the Widow Capet, would be tried in August of 1793. For 32 hours over two days, she would endure the most vicious calumnies – promiscuity, orgiastic excesses, deviant behavior, profligacy, incest, and sexual depravity. She, too, was convicted of treason.

Marie was paraded through the streets of Paris. Her hair had been cut and her hands bound behind her. She was taken by cart to the Place de la Revolution and guillotined at midday on October 16, 1793. She was 37 years old.

Generations would come to believe that Marie Antoinette represented all that was wrong with France. Yes she was a fashion icon, extravagant in her early married years. Yet she was a gracious patron of the arts, a loving wife and mother and had far less political influence than was generally known (or believed). By choice, she curtailed her extravagant habits and was even criticized for her newer simplicity of style and habit.

Letters have emerged showing the kindheartedness and generosity of the queen and as for the infamous quotation, “Let them eat cake,” it is credited to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, from a line in his autobiography Confessions, published in 1766 before the marriage negotiations had begun (in 1767).

Marie Antoinette experienced a tremendous amount of stress and loss in her short life. She was intimidated by a powerful and critical mother who used her as a political pawn. In France, Marie would live surrounded by gossip and intrigue, and condemned by falsehoods. She bravely faced a mob, alone, and witnessed the massacre of members of her household. Grieving the loss of two of her children to illness, she would shortly after bear the sorrow of her husband’s execution, and then bravely face her own.

The priest whispered to her, “This is the moment, Madame, to arm yourself with courage.” She replied, “Courage! I have shown it for years; think you I shall lose it at the moment when my sufferings are to end?”

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Spotify | Amazon Music | Youtube Music | RSS